Creating socially distanced classroom spaces that are equipped for in-person and remote students is a problem Information Technology departments across the country are tackling for the Fall 2020 semester.

When Media Services Technician Steven Mayhugh discovered a small flaw in Eckerd College’s plans this summer, he tapped another staffer to craft a solution that will help faculty and students stay connected.

To facilitate remote learning, Eckerd College purchased Logitech webcams that plug into the instructors’ laptops, 30-foot USB extension cables and tripods. Mayhugh said that as faculty were testing the equipment, they reported that the camera’s signal kept disconnecting from the laptop—even when they weren’t moving the tripod.

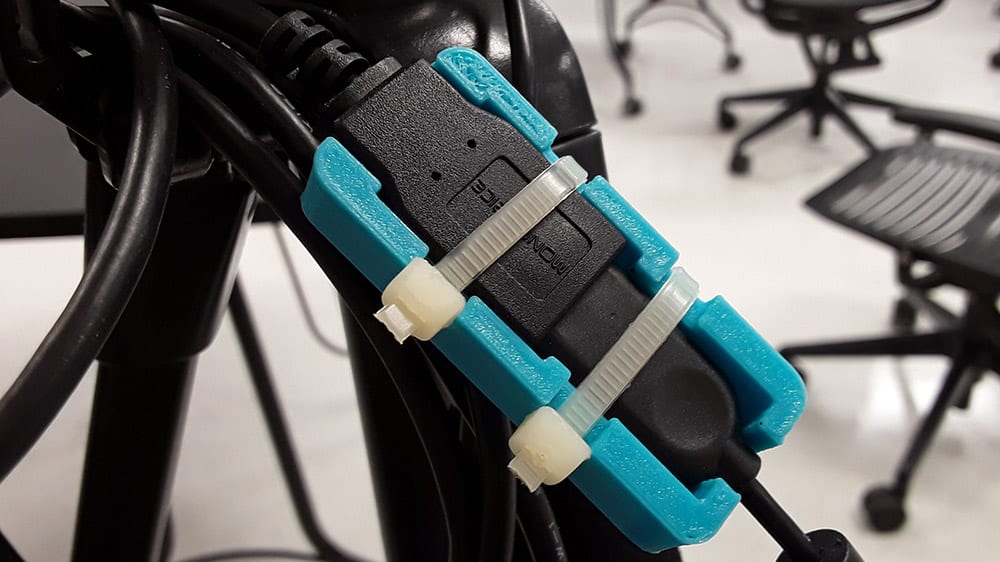

“The extension cable and the camera cable were not a tight fit,” Mayhugh said. “It kept disconnecting while in use.”

He thought he’d once seen a part that could secure the cables together but quickly found there was no piece on the market to address the issue. That’s when he reached out to Physics Shop Supervisor Paul Fratiello to see if something could be made on-campus.

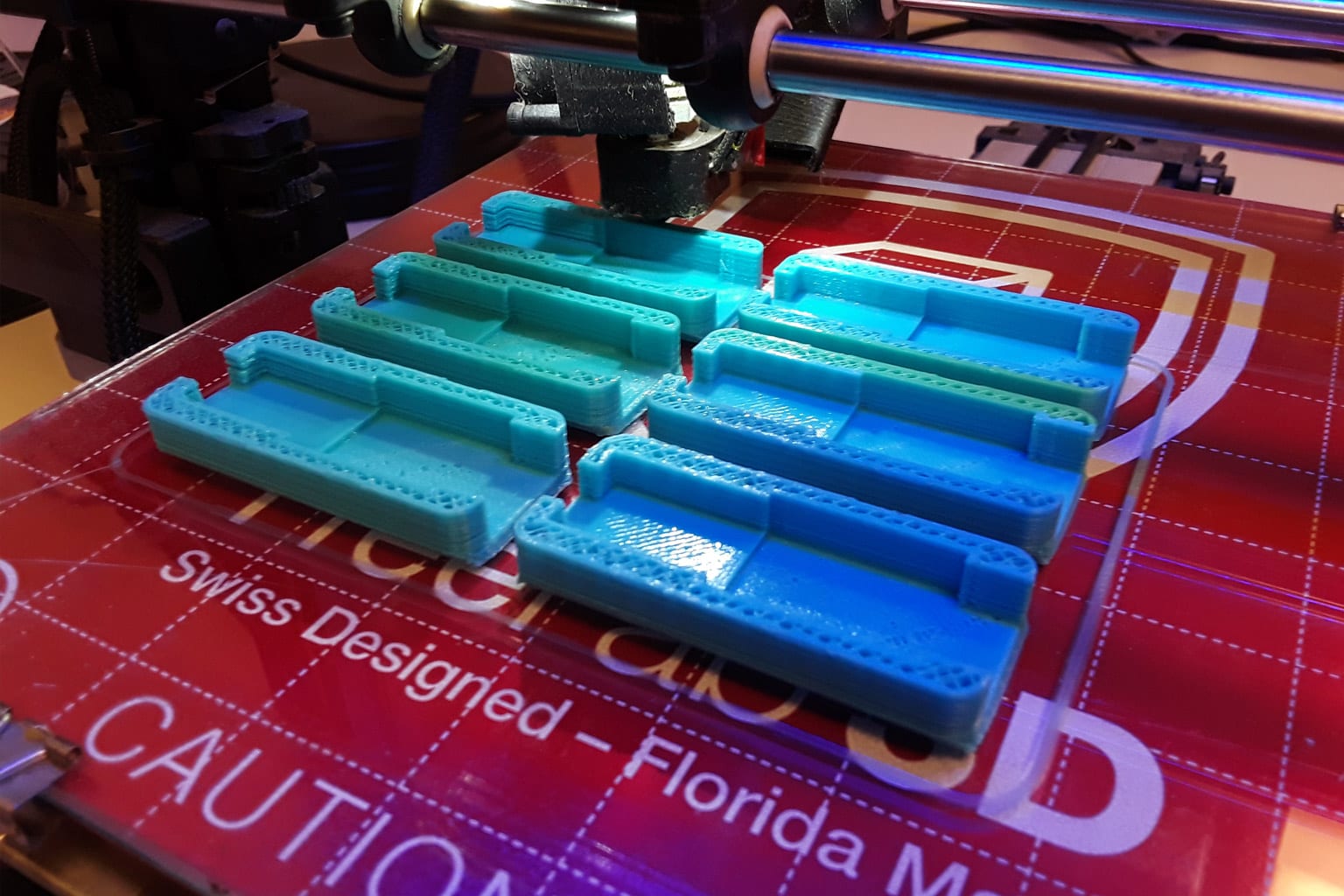

“Once he said what the problem was, I took some measurements and, honestly, designed the thing in 15 minutes,” Fratiello said. The plastic fastener, made with commercially compostable PLA, fits over the connection from the camera to the extension cord and secures them together. Fratiello made a first draft on the Natural Sciences Collegium’s 3D printer, and then after a few measurement adjustments began producing perfect cable fasteners for each of the College’s more than 70 portable webcams.

The plastic fastener, made with commercially compostable PLA, fits over the connection from the camera to the extension cord and secures them together.

Mayhugh said faculty—those that plan to teach remote students synchronously this fall—expressed the need to have cameras they could point at the white board as well as pan around the class during group discussions. Now with Fratiello’s fasteners, they’ll be able to do that, as well as take their classroom setups to outdoor spaces.

The specificity of the new piece’s dimensions and use doesn’t make it a good candidate for patenting or open-source 3D design sites like Thingiverse, Fratiello said. Each piece takes about 30 minutes to print, and each printer can produce six fasteners at a time. In the four years since he joined Eckerd, Fratiello has become adept at using two of the campus’s four 3D printers to troubleshoot issues presented by faculty and staff.

“That’s kind of the beauty of 3D printing. You get to design something, fix mistakes and start again,” Fratiello said.