John Tinsley, a first-year Eckerd College student from Jackson, Mississippi, stood cautiously and asked Michelle Nijhuis the question that had been on his mind.

“You discussed the idea of human overpopulation in relation to limited resources and the decimation of species on Earth,” John said. “Do you think there’s an ethical line crossed when the few get to decide that they have the right to manipulate the rate of reproduction through potential social engineering? And do you feel that there has been a change in the rate of human population, and do you think it has or will change the effects of conservation on Earth?”

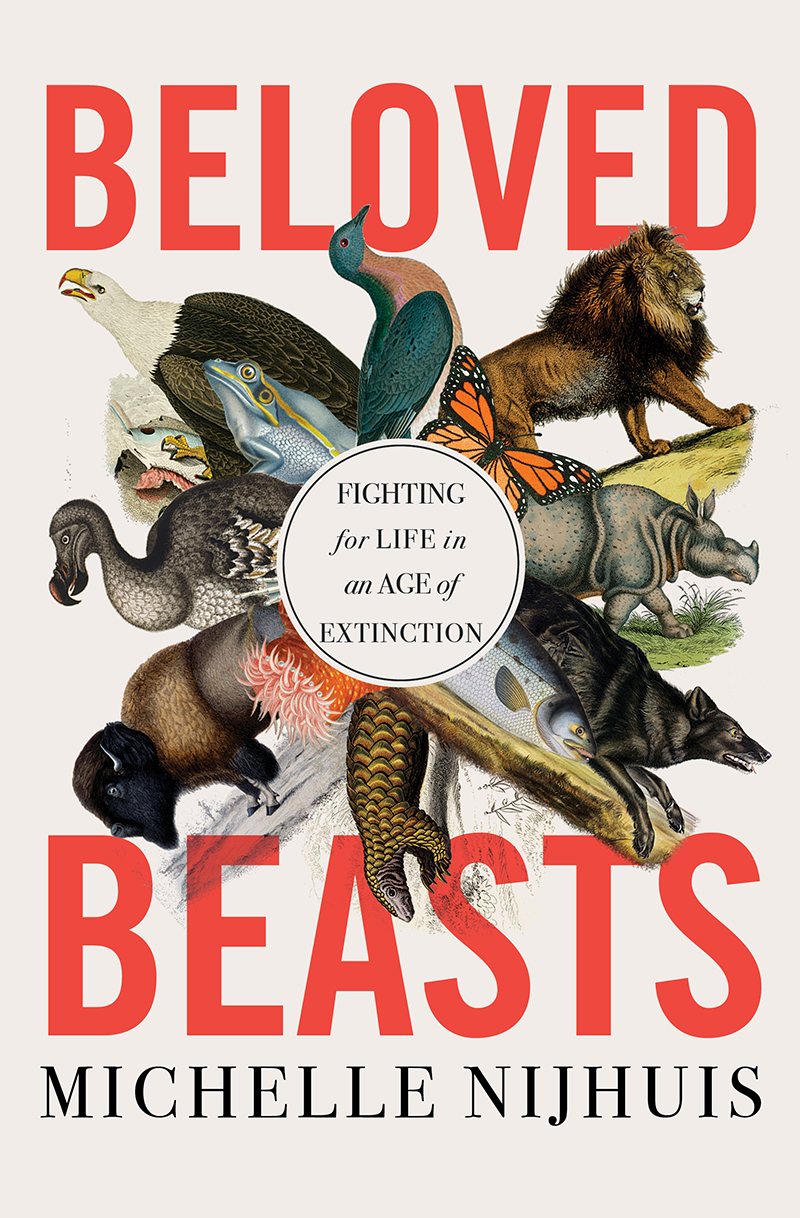

Nijhuis, author of Beloved Beasts: Fighting for Life in the Age of Extinction, answered honestly.

“The best way to reduce the growth rate of the human population on Earth, or to reduce the human footprint, is to educate young women and grant reproductive freedom to all women,” Nijhuis explained. “We know that from experience. It’s been demonstrated many, many, many times over.”

It was a night of big questions about the future of the planet when Nijhuis, the Class of 1968 Visiting Distinguished Scholar, came to Eckerd to discuss her book with first-years, seniors and community members who took part in the College’s annual Summer Reading Series. She gave a lecture on Sept. 10 to a full house in Fox Hall.

Beloved Beasts was adopted as the 2025 Summer Reading Series book by the Foundations Collegium.

Vice President for Academic Affairs and Dean of Faculty Christine Wooley, Ph.D., set the tone for the evening in light of recent national events.

“The role of events like ours tonight, on college campuses everywhere, [is that] we are gathered to learn, to discuss, to question, to disagree and to listen. These are practices that are foundational to a democracy,” Wooley said.

“I am proud to be here tonight, participating in the practices of democracy, and I am grateful to all of you for being here to both witness and take part in these practices.”

Nijhuis is no stranger to the spotlight. She is a renowned environmental writer and a frequent contributor to many journals, national magazines and newspapers—including Nature, Audubon, National Geographic, Scientific American, Smithsonian, the New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker and The Atlantic. Her work in science journalism has received numerous awards—including the American Association for the Advancement of Sciences Kavli Science Journalism Award, a Walter Sullivan Award for Excellence in Science journalism from the American Geophysical Union, an award from the American Association for the Advancement of Science, a media award from the American Institute of Biological Sciences and three separate awards from the American Society of Journalists and Authors.

In her 45 minute lecture, Nijhuis discussed her journey in conservation, starting with her fieldwork on desert tortoises in 1994. She highlighted the historical and ongoing debates over species protection, influenced by factors like money, politics and history. Nijhuis emphasized the evolution of conservation from protecting individual species to ecosystems, citing examples like the Endangered Species Act and the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. She critiqued past elitism in conservation and praised community-based models in Namibia and the U.S. She concluded by advocating for collaborative, community-led conservation efforts to address current environmental challenges.

“There have been layoffs at the Environmental Protection Agency, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration…the Fish and Wildlife Service, and then university research centers that work with these land and water agencies are all under threat,” Nijhuis explained. “These agencies are generational projects. And as a reporter who’s written about them for many years now, I assumed that they were flawed, that they were fixable, and that they were enduring.

It’s been quite a shock this year to realize these institutions that are far older than I am, and that have been around for as long as I can remember, may not be as enduring as I have always assumed.”

Community-led conservation is the future, Nijhuis surmised, citing projects such as the National Wolf Conversation as a step in the right direction. That project brought together stakeholders of diverse viewpoints on the issue of wolf protection and proliferation to a summit where they could discuss big issues and find common ground.

“Certainly, we are not going to agree on every point with one another, but it is possible for us to find common ground, even with people we may have serious disagreements with,” Nijhuis concluded. “And this is urgent work, but it’s also very slow work. It takes a long time. [Passing laws is] relatively easy compared to changing people’s practices slowly over time and changing the way they relate to one another. ”