The title of the course sounds like a classic oxymoron: Serious Comics. But it’s a perfect description of an Eckerd College Autumn Term course where students study serious cartooning, a popular but often overlooked art form where storytelling—and the complex relationship between words and images—is more valued than getting a laugh.

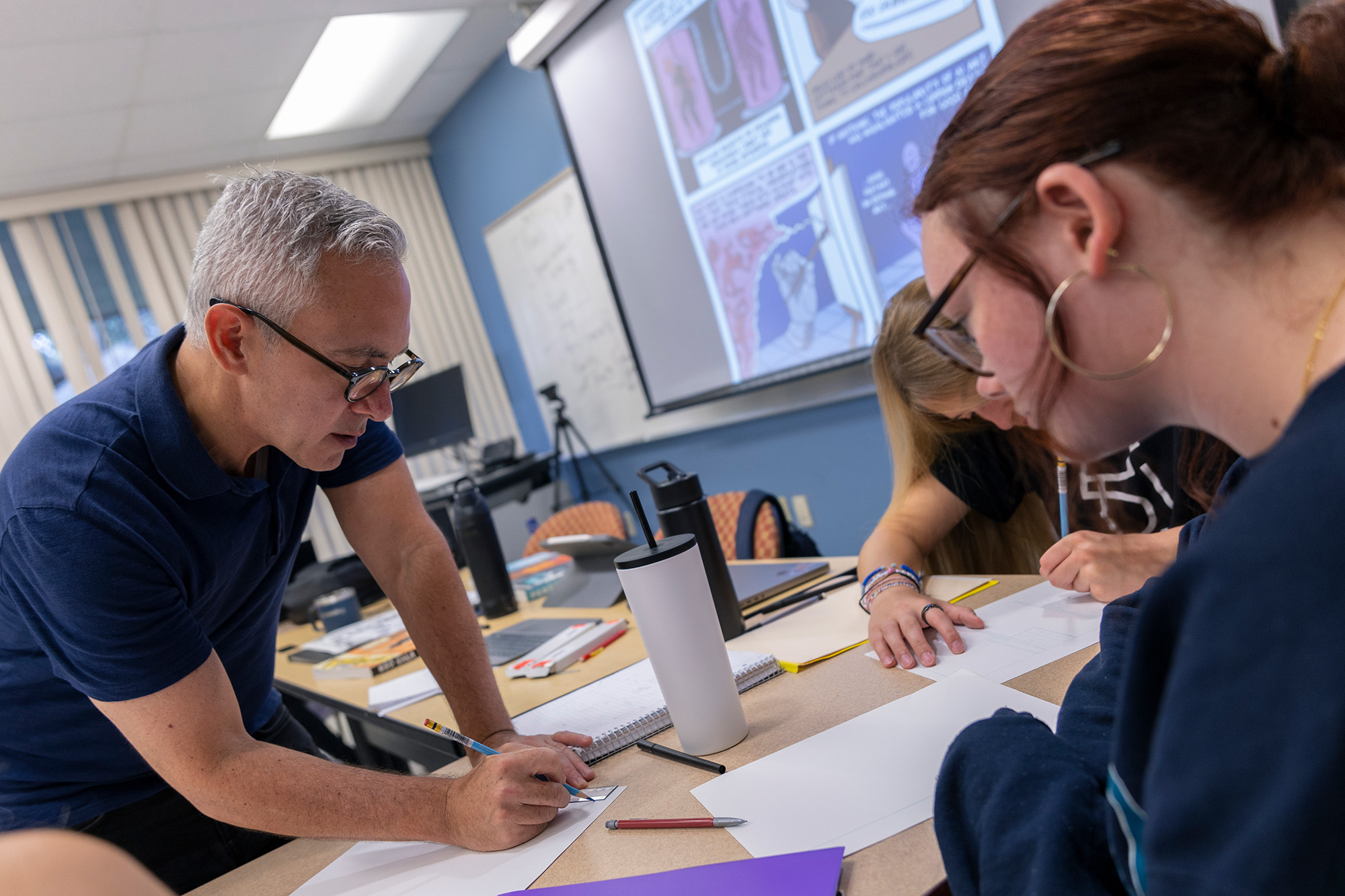

The course has been taught for more than two decades by Jared Stark, Ph.D., professor of literature and comparative literature at Eckerd. He is the author of three books, including his latest, A Death of One’s Own: Literature, Law and the Right to Die (Northwestern University Press, 2018). Among the serious comics that the course examines are ones that focus on the bombing of Hiroshima and its aftermath, the Islamic Revolution in Iran, and the Holocaust. Even the textbook Stark uses for the course, Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, is itself a comic book.

“How can comics that have traditionally been a form of entertainment or escape bear the weight of a painful personal history?” Stark asks. “Part of the challenge of giving voice to such a difficult history is that you need to find a new vocabulary to do that. If the story hasn’t been told before, the vocabulary may not yet exist. Comic artists are particularly good at transforming comics to make it possible to tell previously silenced stories in a new form.”

A Look at The Genre

One of the examples Stark uses is Maus: A Survivor’s Tale, a Pulitzer Prize winning graphic memoir by Art Spiegelman. The groundbreaking book is a collection of cartoons published from 1980 to 1992 and is based on interviews Spiegelman had with his father, a Polish Jew and Auschwitz survivor. In the comic book, Spiegelman depicts Nazis as cats and Jews as mice. “Unlike Mickey Mouse, who always pops up uninjured in the next scene no matter what happens, Spiegelman’s mice have scars and wounds,” Stark explains. “It’s not simply getting the information that the story tells, but it’s a visual representation of telling the story on multiple levels.

“The abstraction of comic book characters allows the reader to identify with that character. As a visual art form comics have the potential to convey empathy.”

Stark explains that more recent serious comics such as Watchmen and Persepolis: The Story of a Childhood, have large followings. “Serious comics,” he says, “began as an underground movement in the 1960s and ’70s. The power of comics to draw readers in and to create an alternative world in which we can inhabit and imagine another’s experience is something that connects all kinds of comics. Comics are a very accessible art form. Once you get into analyzing them, you realize how many layers there are.”

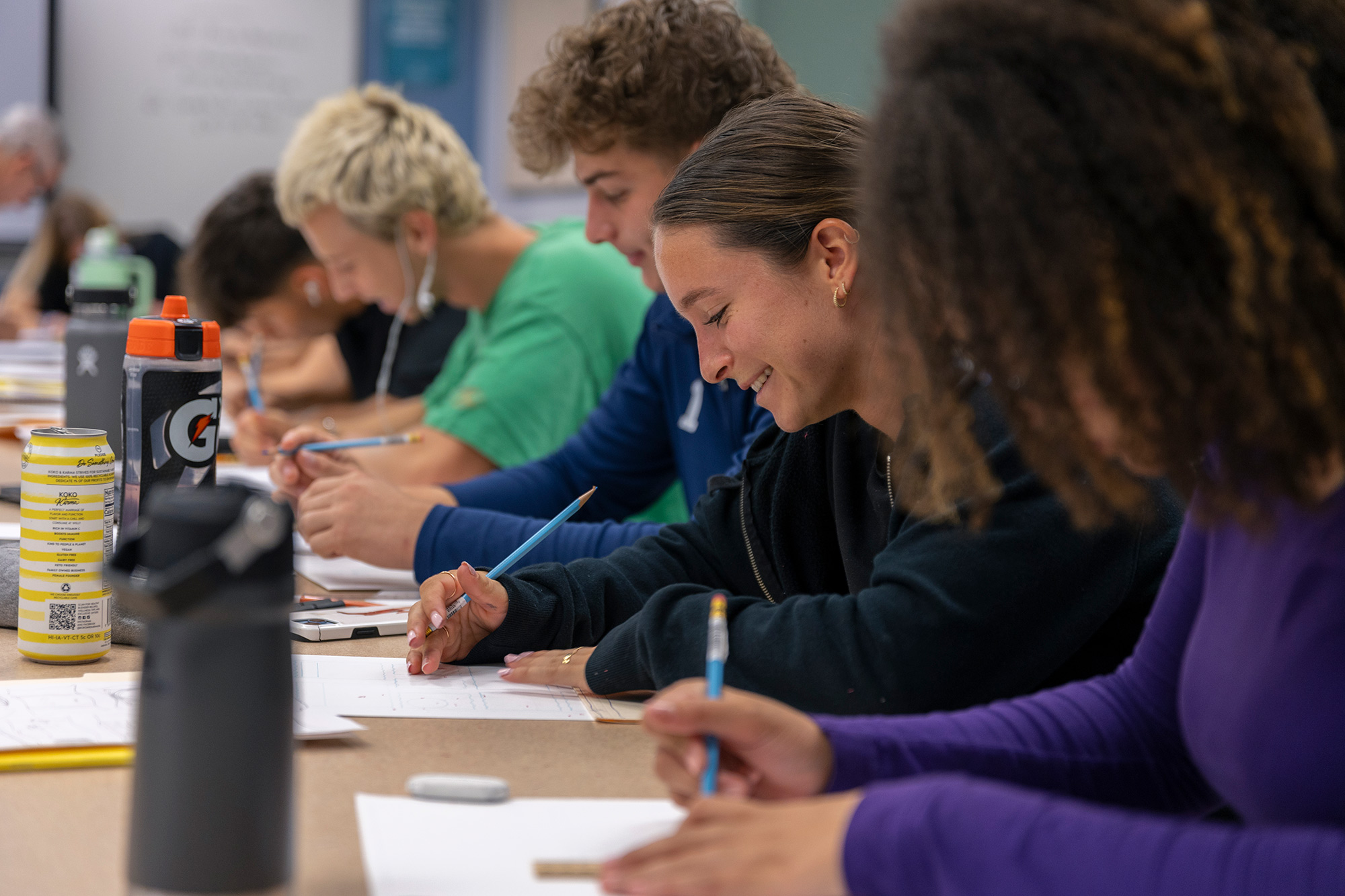

Near the end of the course, students create their own serious comics based on events in their lives. “I want them to explore their own creative powers, to draw their own stories, to be able to think of how to tell a true story,” Stark explains. “Serious really means honesty. How to tell a story or talk about an experience in a way that is really honest.”

The Student Becomes The Teacher

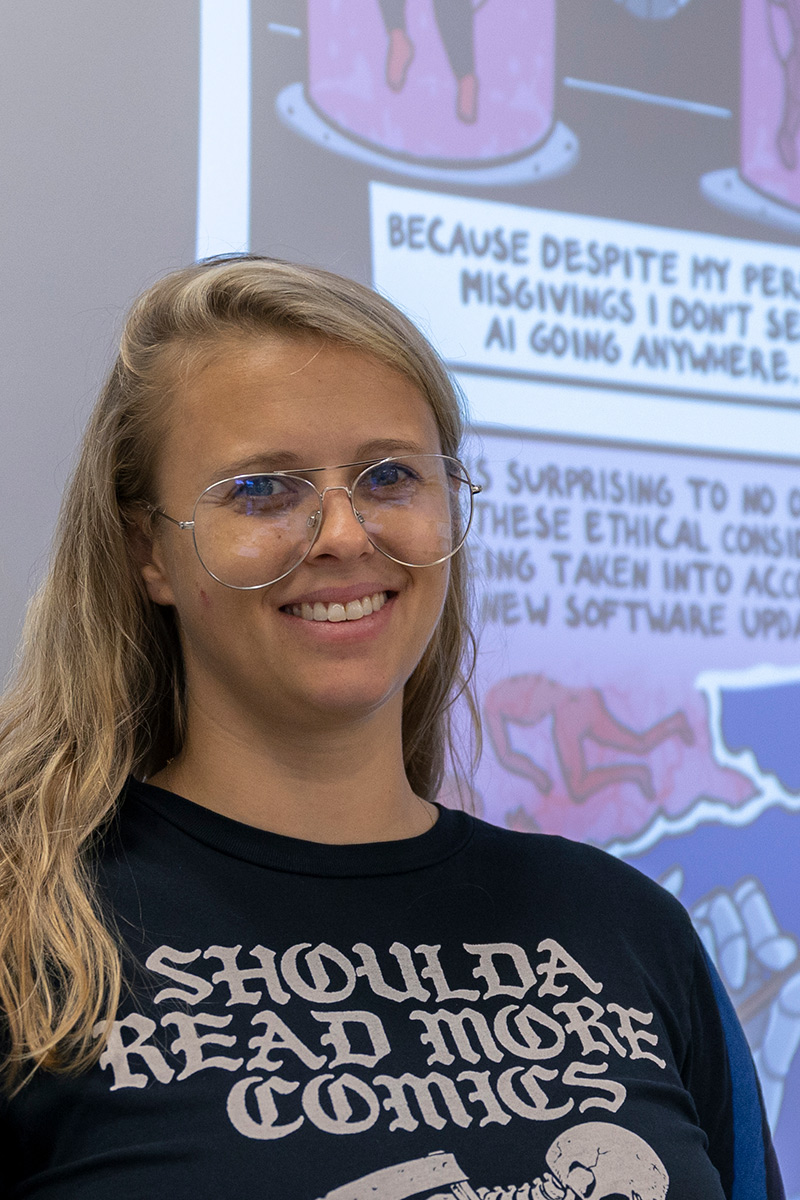

To help him do that, Stark called in an expert—one of his former students. Artist and educator Kristen Shull earned a bachelor’s degree in creative writing with a minor degree in visual arts from Eckerd College in 2010. She followed that with a Master of Fine Arts degree from the Center for Cartoon Studies in Hartford, Vermont, where she currently teaches sequential art. Her comics are regularly featured in Seven Days, a statewide free newspaper in Vermont, where she lives with her husband and daughter. Her visit was sponsored by the Bill and Vivian Parsons History and Literature Program Endowment and the Nielsen Fund for the Humanities.

Kristen, who grew up devouring Calvin and Hobbes, drew one of her first comics for Stark’s Postcolonial Literature course during her senior year. The assignment was to adapt a short story into something else – a poem, for instance. “I ended up drawing a six-page comic book that took much more time than necessary,” she says with a chuckle.

“Comics are one of the most accessible forms of storytelling that we have,” she adds.

“I hope the students walk away with an appreciation of the amount of work that goes into it. There are a myriad of decisions at every step – how much detail, the inking, the script writing.”

“But it’s one of the most satisfying things you can do. And I hope some of the students continue making comics on their own.”

Collectors and Creators

Will Davis, a first-year student from Fairborn, Ohio, has been reading comics since his great-grandfather introduced him to Garfield when he was a child. Now he collects comics. His favorites include One Piece, Black Hole, and Spiderman. “So the course matches up with something I’ve always been interested in,” Will explains.

As for drawing a comic strip, he’ll leave that to the pros. “For the class I drew a short story about something goofy that happened in my dorm the other day,” Will says. “It was fun, but it takes so much time and skill.

“But I’ve learned so much about analyzing comics, which helps me better analyze media in general. Maus was such a beautiful story, but really gut-wrenching at times. Comics can be a serious form of media and should be talked about the same way as other forms. I’d love to see this class as a full semester-long course.”

Unique to Eckerd College, Autumn Term is a three-week extended orientation that allows first-year students to acclimate to campus life before the fall semester begins and upperclass students arrive. First-years take one course for credit during Autumn Term, and the professor for each course serves as the mentor for the students in that class throughout their initial year.