Until the mid-1970s, America had a relatively low and stable rate of incarceration. Then three things changed that.

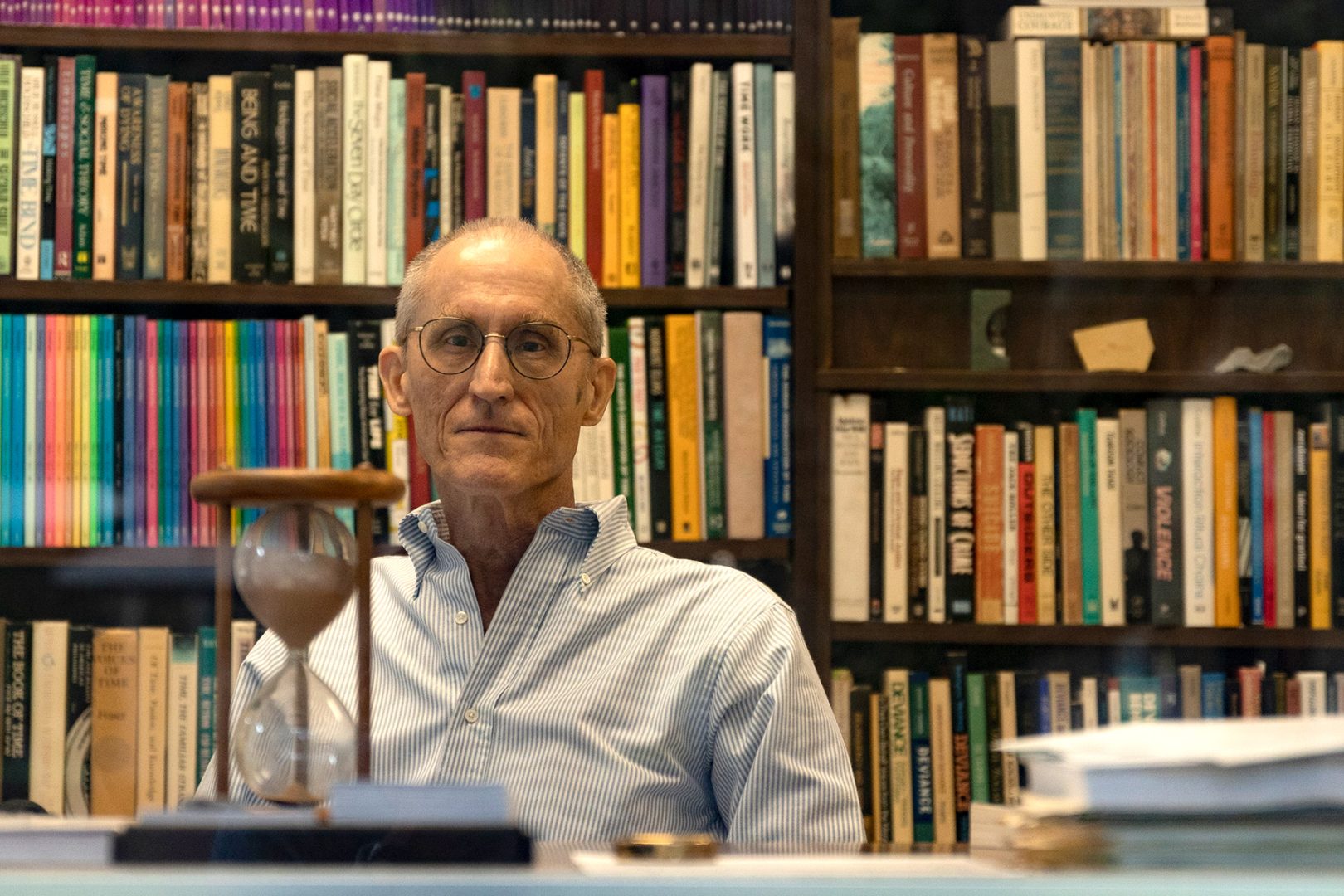

“The war on drugs, the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act happened, and we had mass incarceration—which was a way to reestablish suppression of racial and ethnic minorities,” explains Michael Flaherty, Ph.D., professor of sociology at Eckerd College. “The U.S. now incarcerates more people per capita than any other nation. We have about 5% of the world’s population but about 25% percent of the prisoners in the world.”

The incarceration rate in the U.S. is now just over 700 people per 100,000, Flaherty notes. In the United Kingdom, it’s 148 per 100,000; in Germany, only 77. And of those inmates in America who are released, about 65% return to prison. “It’s kind of a revolving door,” Flaherty says. “The prisons assume the inmates can’t be rehabilitated, so they put no effort in it.”

These are some of the insights offered in Flaherty’s Prisons in America course. The professor first taught the class last spring. This fall, he had to add a second section to accommodate student demand.

Flaherty is a co-author of The Cage of Days (Columbia University Press), a recently published book that examines the prison system in America—including an in-depth account of the 31 years his co-author, K.C. Carceral, spent in prison before being paroled in 2013.

The course examines the origins of the penitentiary system in Europe and its development in the early history of America. In addition to studying the rise of mass incarceration in terms of race and class, students discuss the privatization of prisons and the prison industrial complex in the United States. They also learn how incarceration affects the loved ones and families of prisoners, and explore how prisoners experience time and how they attempt to resist the temporal regime.

“The importance of the course has to do with bringing awareness to what’s going on in the country with respect to the criminal justice system,” Flaherty says. “I don’t think there is enough awareness of what actually transpires. There’s a lot of misrepresentation in various media … movies, television, novels.

“The criminal justice system is often depicted as taking place in a court of law with a lawyer, judge and jury. But most cases are plea-bargained. There’s no jury, no judge. And we have very long mandatory sentencing laws, so now this person is presented with going to trial or pleading out and getting, say, 15 years.”

Flaherty adds that it’s important for students to understand the depth of the racial bias within the system. “Two-thirds of the people incarcerated from 1985 to 2000 were due to drug arrests,” he says. “And 80% of those arrests were for possession of marijuana. These are mostly people being arrested for low-level, nonthreatening kinds of crimes. White young people use marijuana more than Black young people, but Black youths are arrested far more often than white youths.”

Something that’s not widely understood, Flaherty explains, “is that American society generates a lot of desperate poor people who receive little assistance from the government but need to put a roof over their head and food on the table. Jobs they used to get have disappeared, and there’s very little assistance to help them. The rich get richer and the poor get prison.

“Hopefully the students are learning things they will take forward as citizens,” Flaherty concludes.

That, says his student Aleksa Curta, a junior sociology major from Oak Lawn, Illinois, is very likely. “Dr. Flaherty uses good statistical data to get an entire perspective on the disparities,” she says. “You can’t argue against the bias and corruption in the prison system when you have that data,” she adds. “It kind of shook me that [Black people] are more likely to end up in prison than I am for a small offense. It really makes you think.”