In the summer of 1972, gas cost 55 cents a gallon, Don McLean’s “American Pie” and Bill Withers’s “Lean on Me” ruled the radio, five men were arrested for burglarizing the offices of the Democratic National Committee at the Watergate Complex in Washington, D.C., and there was the war in Vietnam.

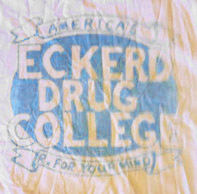

At Florida Presbyterian College, in St. Petersburg, Florida, news of the College’s upcoming name change to Eckerd College prompted some students to print Eckerd College RX for Your Mind T-shirts and plant signs near the campus entrance that pointed to Eckerd Drug College. Graduating seniors worried that potential employers, unaware of the name change, might think FPC no longer existed. Others worried the College would change its focus and direction.

Smack in the middle of all this was Ken Berger ’72. He grew up in Miami and didn’t find FPC—it found him. “They recruited me, and to this day, I do not know why,” he says from his home in Durham, North Carolina. “They had me come up for a visit, and they put me up in a hotel. It was really weird. But I was very grateful.”

His senior year, Berger was an East Asian studies student living in Kappa Complex. He was one of about 200 students in the FPC Class of 1972—the last FPC graduating class. “The summer before, we all got these letters saying the name change was happening,” Berger says. “We were all kind of shocked.

“We knew Jack Eckerd was a very conservative Republican, and FPC was more the opposite. It was really interesting that he supported the College and even featured it in his campaign ads when he was running for governor and the Senate.”

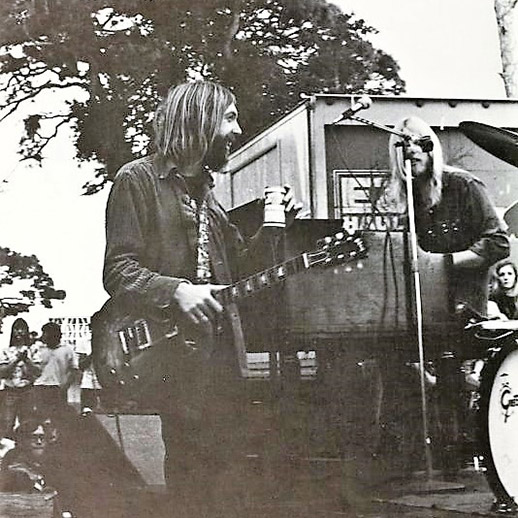

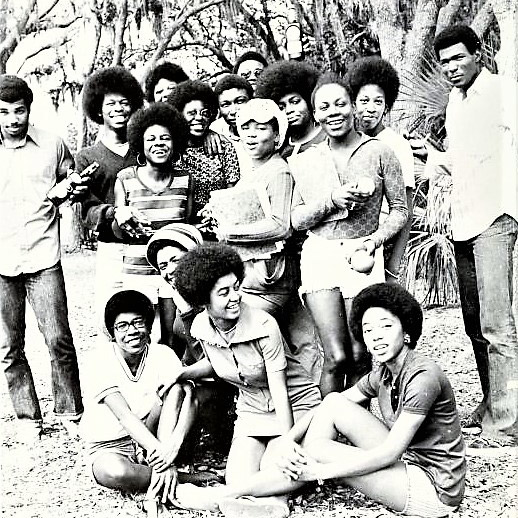

A scene from the Florida Presbyterian College campus, 1972.

Berger says that then–FPC president Billy O. Wireman, aware that students were worried about the future of their college, met with them in 1971 and explained that in addition to Jack Eckerd, he had approached members of the Busch family, owners of the Anheuser-Busch beer companies and the St. Louis Cardinals baseball team. At the time, the family owned a winter home on St. Pete Beach, not far from the FPC campus. “But he [Wireman] couldn’t get past the vice president,” Berger says. “We were concerned whether the College would survive. But everything worked out.”

After graduation, Berger married his college sweetheart, Katie (Tyler) Berger ’73, and eventually retired as a librarian at Duke University, for some 27 years.

“The biggest thing people didn’t want was to have the name change sprung on us,” he says. “And they didn’t do that. I think most people were okay with it. I live with an Eckerd College grad,” he adds with a chuckle. “So it’s fine with me.”

He still owns one of the Eckerd College RX for your mind T-shirts.

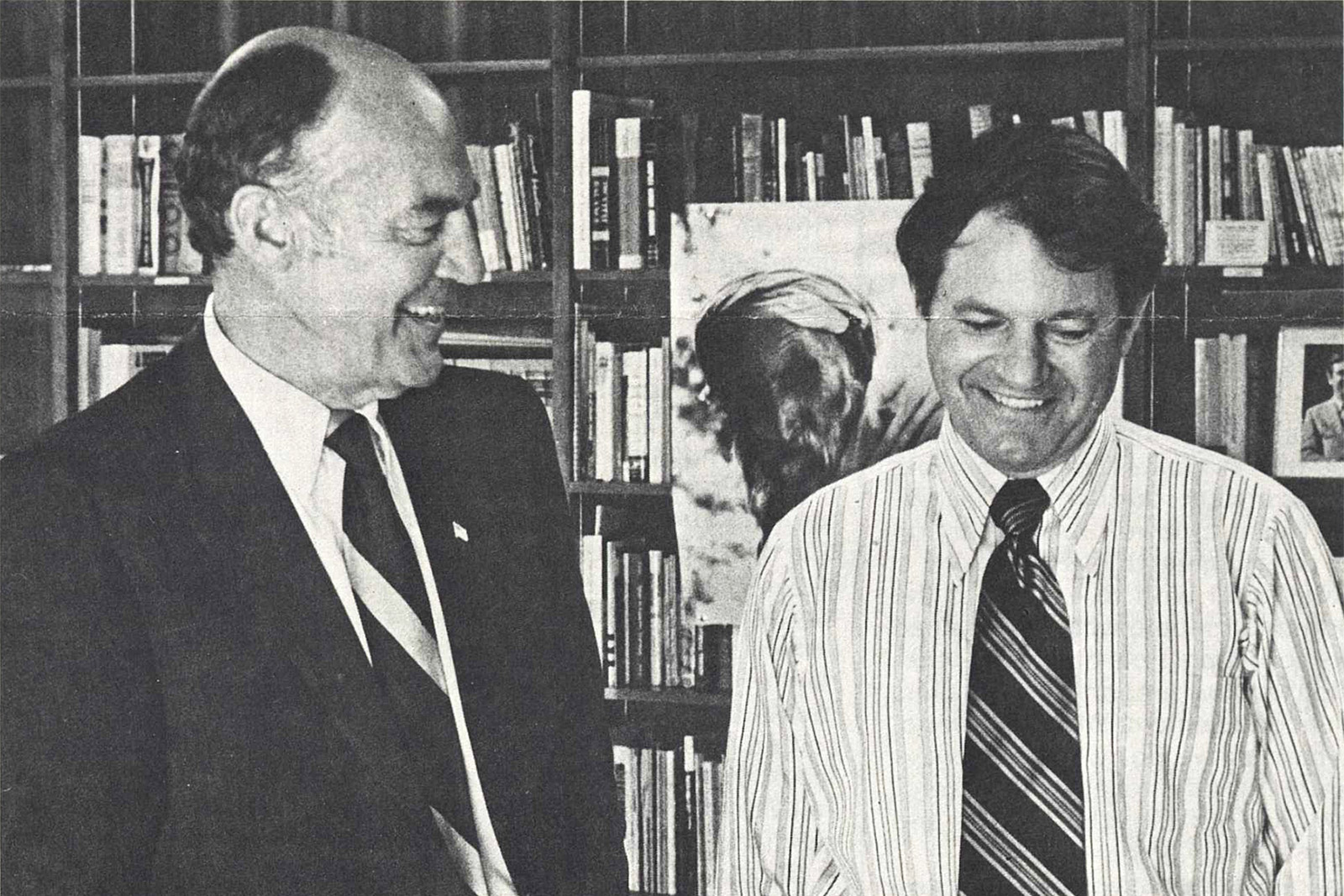

Dr. Billy O. Wireman and the meeting that changed everything

The following is an excerpt from Lessons from the Big Guys by Billy O. Wireman, Ph.D., founding faculty member and president of Florida Presbyterian College/Eckerd College from 1968–77.

I drove to his [Jack Eckerd’s] Clearwater office in early 1971. We greeted warmly and I moved immediately to the issue. “Jack, as a trustee, you know the situation at the College well.” I paused, swallowed deeply, braced my back, and with all the executive and persuasive rhetoric I could muster, continued.

“I have given the College my best shot. We have a splendid academic program with bright students and outstanding faculty. But that huge debt from the early years is killing us. We need help and need it fast.” Then, my punchline.

“As we have talked before, someday the lights will go out on Eckerd Drugs. You will likely merge or be absorbed by a larger company. And the day is coming when you will not be running the company. If you really want to leave a legacy, you will put your name on this college and thus ensure your values in perpetuity. Colleges change their names only once.”

I paused, catching my breath, wanting to finish before getting his response. “The College is high-quality, private, innovative, and has great potential. All the things you stand for. Are there any circumstances under which you would give the College $10 million? If you would do that, it would be an honor for me to recommend that the College become Eckerd College.

“I know you don’t want that, but to be in the company of John Harvard, Leland Stanford, James B. Duke and Cornelius Vanderbilt will be a source of joy and pride for your friends and family.” I stopped, waiting for his response. It came in a surprising question: “Will $10 million do it?”

“We will need a lot more, but this would pay off the short-term debt and give us a base endowment from which to build,” I responded. His next response was less encouraging. “I probably won’t do it, but it is an interesting idea.”

Several agonizing months passed, Wireman wrote, before he received a phone call from Eckerd, the head of a chain of 229 drug and 20 department stores in six states. “Billy, sometime when you have a minute, come by,” Eckerd said. “I have reviewed your proposal … I still probably won’t do it, but let’s get together.”

After that meeting in June 1971, Eckerd agreed to make a $10 million gift to Florida Presbyterian College. It was, at that time in Florida’s history, the largest gift from an individual to a college or university. “The name change,” Wireman noted, “was not a condition of the gift …. On my recommendation, Florida Presbyterian officially became Eckerd College on July 1, 1972. On that occasion, Jack Eckerd told Fortune, “This is the best investment I ever made.”

An FPC student but an Eckerd College graduate

Katie Berger ’73 is one of the relatively few people who can say they enrolled in FPC but graduated from Eckerd. In the summer of 1971, when word of the name change reached campus, she was a sophomore from Richmond, Virginia, who was living in Delta Complex. “I had a big interest in marine biology from middle school on,” she says from her home in Durham, which she shares with husband Ken, a member of the last FPC graduating class.

“There was a feeling on campus that summer that the financial state of the College was not great,” Katie explains. “And when the name officially changed at the end of my junior year, by that time you’re starting to focus on getting out of college. I thought that if Jack Eckerd wants to give us the money, so be it. All of us realized how hard it would be to explain to a potential employer that the college you just graduated from is no longer there. That’s not a good feeling.”

After Katie and Ken got married in 1973, they each earned a master’s degree at Florida State University, and she worked in biochemistry and DNA labs at the University of North Carolina. The couple also raised two children.

From its beginning, FPC had held open the possibility of renaming the College in recognition of a financial commitment such as Jack Eckerd’s.

“When the name Florida Presbyterian College was adopted, it was understood that this was an interim name chosen to be used until such time as another name might be chosen,” the late Rev. Paul M. Edris, an FPC Board of Trustees member and pastor of the First Presbyterian Church in Daytona Beach, said in a 1974 interview.

Was the name change a condition of the gift?

Jack M. Eckerd’s $10 million commitment to the College raised his total giving to the institution at the time to more than $12.5 million. The gift was seen as a much-needed boost, if not a lifeline. Money to keep the College afloat had become the primary concern for Wireman and the FPC board.

“The 1970s were a tough time for liberal arts colleges all over the country,” the late Sarah Dean, FPC’s dean of women, told an interviewer. “We really did think at one point we were going to go under. We thought we would merge with the University of South Florida or New College in Sarasota. It was just one crisis after another.”

“When Jack Eckerd, at that time having served for seven years on the board, worked out a plan for making a contribution to the College in the amount of some $10 million, in addition to what he had already given, there was nothing—and I wish that there were some way that people would understand this—there was nothing said in the agreement about changing the name of the College.

Jack Eckerd, 58 at the time, issued a statement after the announcement. “I am deeply honored by the action of the Board of Trustees,” it reads. “I want to reiterate my original statement that the financial commitment which I made had no strings attached whatsoever. My sole purpose in making this commitment was to help insure this very promising institution’s future and to emphasize my opinion of the importance of this type of college in assuring the growth and development of our nation’s future leaders.”

Who was Jack Eckerd?

Born in 1913 in Wilmington, Delaware, Eckerd’s mother died suddenly when he was 10. During World War II, he was a decorated bomber pilot who logged nearly 2,000 hours of flying time. And in 1952, he bought three failing Tampa Bay–area drugstores. He was not a college graduate; he learned the business by working with his father, J. Milton Eckerd, who owned drugstores in Pennsylvania and other parts of the Northeast. He learned well.

At its peak in the early 1980s, Clearwater-based Jack Eckerd Corp. was the nation’s second-largest drugstore chain and the Tampa Bay area’s largest locally owned business. Sales reached $5 billion a year. But making money wasn’t the only objective. Jack Eckerd also desegregated all Eckerd lunch counters in 1961, three years before the Civil Rights Act required it. And according to the St. Petersburg Times (now Tampa Bay Times), “He tried to visit every store and every employee at Christmastime.

“He even kept a personal listing in the Clearwater phone book so customers could call him at home. His children called it ‘the nut line.’”

Eckerd sold his stock and resigned as the company’s CEO in 1986. Ownership passed to the company’s employees and other investors until 1997, when J.C. Penney Co. bought them out. The end came in 2004, when after seven years of sluggish performance, J.C. Penney sold 1,200 Eckerd stores to CVS Corp. and more than 1,500 others to the Jean Coutu Group from Canada.

In the meantime, Jack Eckerd had spent the last decades of his life giving away much of his estimated $150 million fortune to causes close to his heart. Along with his wife, Ruth, he supported several charities in the Tampa Bay area, including Clearwater’s Ruth Eckerd Hall and wilderness camps and rehabilitative programs for children.

He also was a force in Republican politics, running twice for governor and once for U.S. Senate. He was defeated each time. Later, Eckerd served as director of the U.S. General Services Administration under President Gerald Ford. In 1981, he was chosen to run a Florida program that taught job skills to inmates by creating prison businesses.

A passionate sailor, he won the Nassau Cup trophy in 1967 aboard his 52-foot yawl Panacea. He also was deeply religious, a member of the First United Methodist Church of Clearwater.

Jack Eckerd died on May 19, 2004, after contracting pneumonia. He was 91.

According to his obituary, he once told a reporter when asked about having the school named after him, “At first, I thought, ‘Oh no, everyone will misunderstand.’ But then I thought, ‘Oh, what the hell … I’m a human being. I admit I’ll get a terrific kick out of it.’”

Billy Wireman died the following year at age 72. In his obituary, it was noted that a month after the name change announcement, a Times reporter asked Wireman if the College was “out of the woods financially?”

“No, we are not,” he answered. “But we have a fighting chance for the first time in our history.”