Call it a tag-team mission to help rescue the coral reefs that surround Florida. A group of students from Eckerd College is in the Florida Keys studying the Caribbean king crabs that graze on the coral reefs.

Another Eckerd group also is headed to the Keys to learn how to make the corals themselves more resilient to rising seawater temperatures, salinity changes and other stressors.

The team studying king crabs is led by Eckerd College Assistant Professor of Marine Science Philip Gravinese, Ph.D., while the group working with the corals is led by Associate Professor of Marine Science and Biology Cory Krediet, Ph.D. Funding for both efforts was provided by “Protect Our Reefs” License Plate grants from Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium and Eckerd College. For every specialty plate sold, Mote receives a direct $25 donation that goes straight into supporting projects that benefit Florida’s coral reefs.

Gravinese received $32,000 from Mote for his project, while Krediet received $30,000 from Mote and $4,500 from Eckerd.

For the second year in a row, Gravinese and several of his students will spend more than two months in the Keys trying to find out how well Caribbean king crabs can tolerate rising ocean temperatures. That’s crucial because if the crabs can take the heat, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration would like to relocate about a million king crabs to the coral reefs surrounding the Keys.

Gravinese and his students are studying Caribbean king crabs because the animals graze on macroalgae that in recent years has been devastating to the reefs. But if the crabs also are stressed by warming waters, the effort could be jeopardized. Gravinese explains that the crabs act like lawn mowers. They graze on algae and they don’t disturb the coral. “Sea urchins and parrotfish also eat algae,” he says, “but they scrape away coral tissue. Crabs don’t.”

The Eckerd teams are stationed at Mote Marine’s Elizabeth Moore International Center for Coral Reef Research & Restoration on Summerland Key. Gravinese, in collaboration with Jason Spadaro, Ph.D., staff scientist and program manager of Mote’s Coral Reef Restoration Research Program, titled this year’s project The Effects of Elevated Temperature on the Swimming Ability of Caribbean King Crab Larvae: Implications for Modeling Grazer Recruitment for Coral Restoration.

In their submission to the Mote Marine Laboratory, Gravinese and Spadaro explained that “the Caribbean king crab, which primarily grazes on macroalgae, has attracted the attention of restoration managers as a possible species to reduce algal cover on Florida’s patch reefs and is a part of NOAA’s Mission: Iconic Reefs restoration. Experimental evidence indicates that the presence of king crabs on Florida reefs not only reduced algal cover by 85% but also resulted in two to three times more juvenile corals.

“While these results show promise for the consideration and utilization of this species, the restoration plan assumes that king crabs will be able to tolerate extreme temperatures, especially during their often more sensitive earlier life stages.

“Despite the call to stock king crabs onto Florida’s reefs,” the submission continues, “no studies have assessed how thermal stress may impact the vertical swimming ability of their larvae. This is important because king crab larvae may elicit vertical swimming migrations, which can affect their horizontal transport and dispersal when currents are depth-stratified.”

As Gravinese and Krediet point out, the loss of coral reefs is not only an environmental concern; there could be serious economic impacts as well. NOAA estimates that coral reefs in southeast Florida have an asset value of $8.5 billion—generating $4.4 billion in local sales, $2 billion in local income and more than 70,000 jobs.

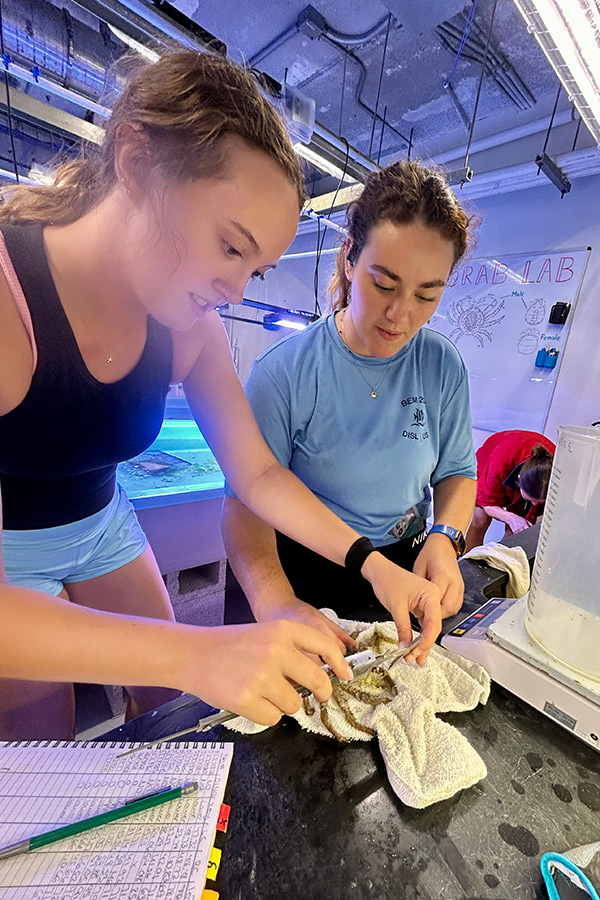

Taylor Queen, a senior environmental studies and marine science student from Athens, Tennessee, and Gillian Smith, a junior marine science student from Indianola, Iowa, work in Gravinese’s Ecophysiology Lab and are part of the Eckerd team. Last summer, both students conducted similar research with Gravinese and other Eckerd students at the Mote Lab.

Taylor and Gillian designed and implemented their own projects, and both plan to highlight their research in the Keys when selecting a graduate school. Taylor is monitoring crab larvae to see if they are swimming up or down in the water column in response to higher temperatures. Depending on which direction they take, she says, the larvae could remain on the reefs or be carried away by currents.

“Designing my own project has really helped me prepare for my career in research,” Taylor says, “and it’s something that’s made me even more determined to continue this work. It’s one thing to learn about climate change and another thing to actually see it in person. I was here during the heat wave in 2023, retrieving corals that had been bleached. So I’ve seen the impact.”

But there is hope, Taylor says, in large part because sharing information is a key part of Mote’s—and Eckerd’s—mission. “I get to meet with research scientists every day. They ask what I’m working on, and they tell me what they’re doing. The reefs are gorgeous, and we’re all really invested in protecting them.”

Another vital element in the success of a relocated crab population is location. Gillian is examining and comparing adult crab populations in the Upper Keys with those in the Lower Keys to see if one population is more resilient to rising temperatures than the other. She is taking blood samples and monitoring respiration of the crabs, all part of a project she designed.

“I will have so many skills from what I’ve learned by doing our own research projects,” says Gillian, who also plans to attend graduate school. “We have to decide what we should or shouldn’t do, and then try it. It really helps us grow.

“What I’m doing gives me so much hope I can make a difference,” Gillian adds, “and that the results can help the coral reefs. It’s difficult sometimes, but I feel like I’m doing important research.”

Krediet and his team also are building on research he and Eckerd students previously did in the Keys. This year’s project is titled Microbiome Manipulation: Beneficial Microorganisms of Coral as a Tool to Increase Coral Resilience. The research is a collaboration between Krediet and Mote Marine’s Erinn Muller, Ph.D.—associate vice president for research, program manager for coral health and disease, and senior scientist—and Celia Leto, senior biologist and coral reproduction laboratory manager.

In their proposal, Krediet and the Mote scientists state that their aim is “to contribute to the development of sustainable biological control strategies to manage bacterial diseases of corals, especially during restoration efforts. This proposal continues to build on our previous observations and results that specific genotypes of (coral) are more resilient to disease than others and that their resilience may stem from their associated microbiomes.

“Our previous work, including preliminary results from our last Protect Our Reefs funding in 2022, indicates that corals may specifically recruit beneficial bacteria that aid in their overall health and immunity, especially assisting in resistance to coral pathogens. In this current proposal, we will continue to characterize and refine cocktails of beneficial microbes of corals associated with two apparently disease-resistant genotypes of (coral).”

Key here are microbiomes, they say, which are all the microbes—such as bacteria and viruses—that are naturally found in the body of a plant or animal. They can contribute to health and wellness in many ways. The best analogy, Krediet adds, is human use of probiotics.

“We’re hoping to introduce beneficial microbes onto corals that don’t already have them,” he explains. “The original grant was targeting existing adult corals with fully formed microbiomes. We are now taking a new approach and using juvenile corals. During their first four months, the microbiome is naive. It’s a really novel approach that’s never been attempted before—establishing a beneficial microbiome early on rather than later in the coral’s life.”

Krediet’s cohort will work on campus and then visit the Keys in August. They will return to the Keys in December to inoculate juvenile coral with microbes they want the coral to have.

“We think this is really important,” he adds. “Right now a lot of coral restoration involves looking at cloned fragments back on the reef. That’s an involved process to manipulate their established microbiomes. We think by targeting the juveniles, which are tiny, we can potentially grow thousands of juvenile coral that already have the microbes that could help them once outplanted on the reef.

“Healthy corals mean healthy reefs,” Krediet says. “About 25% of all marine life in the ocean depends on coral reefs, and if we want corals to be around, we have to start identifying the mechanisms that help them survive the changes we’re seeing.”

The three students working with Krediet are Aidan Hess, a senior marine science student from Atlanta; Grady Burling, a junior marine science student from Concord, Massachusetts; and Jayden Kuhn, a senior marine science student from Whitehall, Pennsylvania.

“We’re hoping to see how large an effect introducing microbes will [have] on the coral and how it can survive,” Aidan says. “With changing climate conditions, we’re trying to better understand the effects and how we can lessen our biological impact on corals.”