When a person walks into Living Roots Eco Design in St. Petersburg, Florida, Savannah Core ’22 can walk them through the process of landscaping spaces with Florida’s natural environment in mind.

As the head production manager of the business’s nursery, Core cares for the plants on-site, consults with customers on projects, and offers education to clients and a cluster of children’s group home residents who attend her weekly gardening class. It’s almost like she’s back at the Eckerd College Community Farm.

“I started with marine science, but the environmental science stuff really drew me in,” says Core, a biology graduate from Abita Springs, Louisiana. “When I saw the garden [which became the Eckerd College Community Farm], I fell in love with growing food.”

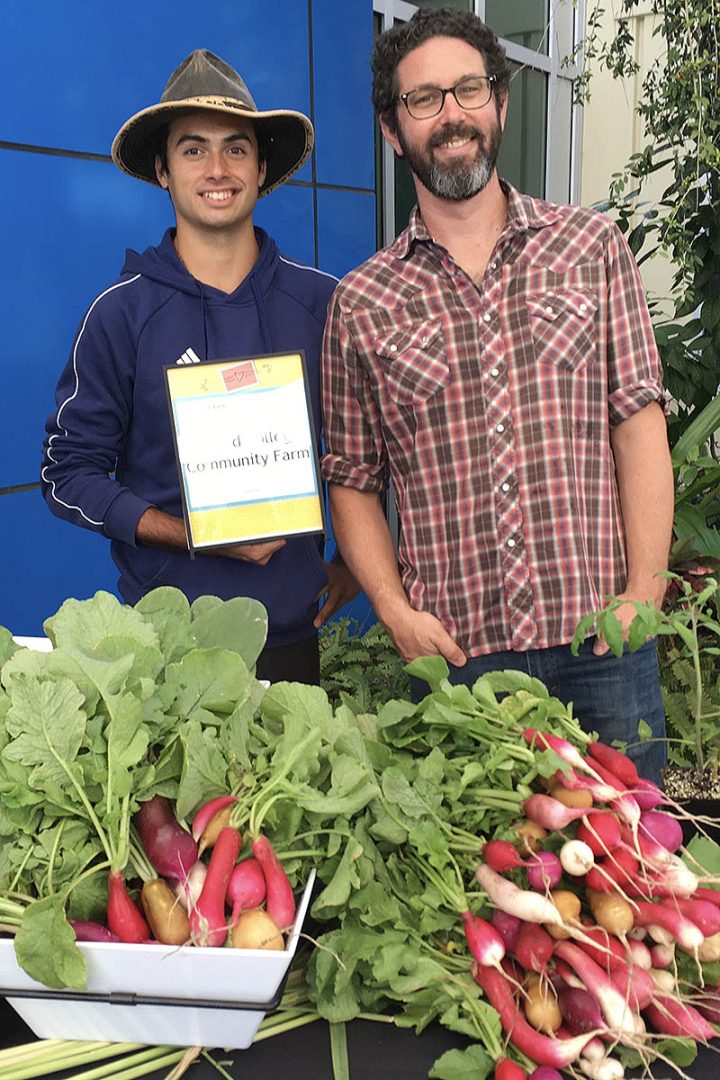

Core served as an EC Community Farm ambassador her senior year—leading tours, working on plantings, and brushing up on the science behind growing things with faculty members and Farm Manager Jon Prieto. The farm employs students as ambassadors, composters and assistants throughout the academic year, so they gather experience in every aspect of running a liberal arts farm.

Since its grand opening in October 2021, the farm has generated several new on-campus jobs that train students for careers in the burgeoning urban agriculture industry, says EC Farm Faculty Director, Environmental Studies Instructor and Internship Coordinator David Himmelfarb, Ph.D.

Any Eckerd student can volunteer for workdays on the farm—learning to seed, weed and harvest as they explore the science behind biodiversity versus monocultures and the importance of native species.

Last spring, the farm produced 500 pounds of produce that was served in the campus cafeterias—and it is on track to exceed that harvest this fall.

“I think it’s really a great place to start to get hands-on experience and translate their skills to a more commercial application,” Himmefarb says. “They also get to do a lot of different things, and the range of responsibilities is greater as well as the opportunities for growth.

Core also helped create the Banana Bike, a uniquely Eckerd event where farmworkers distribute the campus’s bumper crop of bananas via Eckerd yellow bikes and stir up student excitement about the farm in between classes. The memory is so great, she even got a tattoo of the two-wheeled sustainability promoter.

“I knew I wanted to get an Eckerd tattoo after graduation,” Core says while laughing. “The yellow bikes are really iconic, so getting the banana bike that incorporates my love for the farm was even better.”

Shyann Oglesby, a senior environmental studies and animal studies student from Liberty, South Carolina, took Himmelfarb’s Food and Sustainability class and really liked the parallels between what she knew from her family’s small farm to what was happening on the campus’s 1-acre plot. As a farm ambassador, it’s her job to know what’s happening and why—from in the fruit tree grove to the newly installed tea garden. She uses that knowledge in her off-campus volunteer activity at the Edible Peace Patch, where college students teach elementary schoolers gardening basics at their schools.

“I want to be a teacher,” Shyann says. “I want to do all kinds of place-based learning. And studying in the farm and giving tours makes it easier for me to identify and talk about the plants when I’m volunteering at Peace Patch.”

Eliza Hensel ’22 served as the compost manager from before the farm’s launch until her graduation, and now she counts composting as one of her many duties as assistant manager at St. Petersburg’s The Urban Harvest. With a tip from EC Farm Manager Prieto, Hensel applied and started working part time during her senior year and transitioned to full time a week after graduation.

“It gave me such a sense of relief and a boost of confidence to have a job lined up, because that was one of my biggest concerns,” says Hensel, an environmental studies and animal studies graduate from Highland Park, Illinois. “This has given me such a great first step in this field … a sense of excitement to be able to take on the next step knowing I had a job when I walked across that stage.”

In her spare time, she also manages her nonprofit, Blue Bucket Compost, which gathers food waste from Gulfport, Florida, restaurants and donates the compost created to a community farm north of Boyd Hill Nature Preserve.

“It’s going really well and eventually we will get incorporated and grow,” Hensel explains.

Current EC Community Farm ambassadors can follow the trajectory of their predecessors and look forward to the opportunities that await them after graduation.

Aaron Chimelis started working in Eckerd’s community garden to get closer to his Puerto Rican jibaro roots, and discovered a love of food sovereignty that made him want to learn even more.

“My job on the farm has elevated my knowledge. I now have more food sovereignty because I know where [my food] comes from and how it was produced,” explains the senior environmental studies and communication student from Port St. Lucie, Florida.

His big dream is to be a documentary filmmaker who focuses on indigenous cultures and how they adapt, or don’t, to the changing landscape, including their agricultural heritage—but he’d love to keep working in and learning about farming as he films.

“A lot of community farms falter in the first two years, but the Eckerd garden has been in operation for the last 10 years and grown to be the farm because of the dedication of a few faculty and students,” Aaron says. “If students want to come out and join the team, they should understand the knowledge and the history of the place. It’s more than just a job. You are part of a movement to understand food.”

Himmelfarb agrees and says that the farm’s liberal arts approach uniquely prepares students for careers after college.

“The way that we think about food production is a more holistic approach. We trace everything from history to economics to chemistry to biology to politics in our work,” he explains. “It’s not just about growing food, but how those actions fit into a broader system. It enables them to do a lot of different things.”